Although it has already been explained that the Llama model and the Llama License (Llama Community License Agreement) do not, in any sense, qualify as Open Source, it bears noting that the Llama License contains several additional issues. While not directly relevant to whether it meets Open Source criteria, these provisions may nonetheless cause the license to terminate prematurely in practice. Much of what follows may overlap with points raised in my other articles on Llama’s Open Source status. However, the present discussion focuses on the dangers arising from those issues, in no particular order.

This text is primarily intended as a guide to potential risks associated with the use of Llama models for companies, engineers, and compliance personnel considering the development of derivative Llama-based models or integrating Llama into their own services. It does not constitute legal advice regarding any specific usage scenario. Should more in-depth interpretation or advice on practical issues be required, consultation with a professional knowledgeable in U.S. contract law and California law is recommended.

Original Japanese Article: https://shujisado.com/2025/01/20/llama_license_risk/

- 1. A Bilateral Commercial Contract Rather Than a One-Sided Permission License

- 2. Can Companies Disregard the 700 mil MAU Restriction? Concerns Regarding Aggregate User Counts

- 3. Do Mid-Sized or Smaller Enterprises Need Not Worry About the 700 mil MAU Restriction?

- 4. Must Subsidiaries, Parent Companies, or Affiliates Also Comply with the Llama Acceptable Use Policy?

- 5. How Far Do Contractual Obligations and Compliance with the Acceptable Use Policy Extend?

- 6. Must New Clauses in the Acceptable Use Policy Be Observed If It Is Updated?

- 7. What Risks Arise When the Acceptable Use Policy Is Updated?

- 8. May One Apply Local Law in Interpreting the Acceptable Use Policy?

- 9. Does the Llama License Extend to Model Outputs and Models Trained on Those Outputs?

- 10. Conclusion

- References

1. A Bilateral Commercial Contract Rather Than a One-Sided Permission License

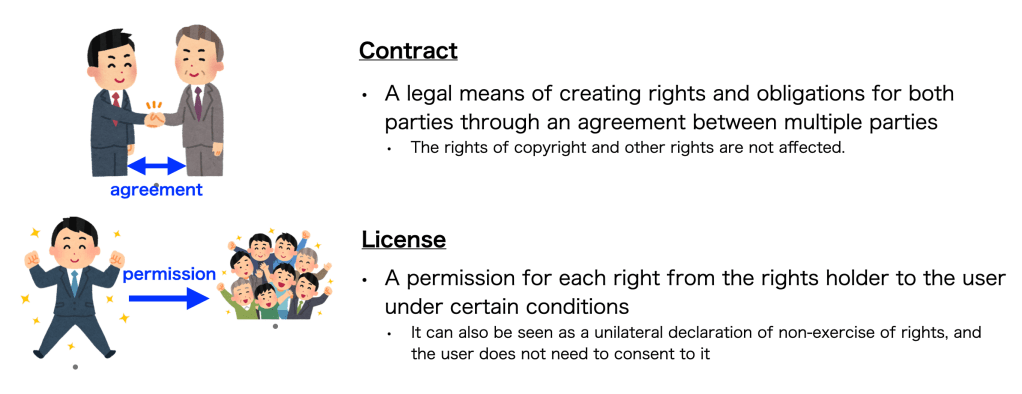

First, as a premise for this discussion, one must recognize that, in legal terms, the Llama License is not a conventional copyright license aligned with Open Source principles; rather, it functions as a bilateral contract in a commercial transaction context. The very title, “Llama Community License Agreement,” as well as the definition of “Agreement” at the start of the contract text, affirms its contractual nature. Through the mechanism of a click-through acceptance or by using Llama, the Licensee is made to consent to be bound by the contract. Furthermore, throughout the agreement, obligations are imposed on the Licensee that exceed the scope of Meta’s underlying intellectual property rights, clearly indicating a contractual rather than purely copyright-based framework. Indeed, Meta requires the user to sign off or otherwise affirm the contract when downloading the model, underscoring that the arrangement is a two-party commercial transaction governed by U.S. contract law between Meta and each Licensee—rather than a mere copyright license.

Open Source refers to a license (or software distributed under such a license) that grants freedom to perform certain exploitation acts—such as reproduction, adaptation, distribution, and public transmission—under various national copyright statutes or equivalent legal frameworks. In other words, it is a unilateral legal declaration whereby copyright holders elect not to exercise certain rights or restrictions and instead grant broad freedoms to all users. While several U.S. court rulings have acknowledged that open licenses can have contractual force, compliance in everyday practice generally views them as unilateral statements of free use, not involving bilateral negotiation or consideration.

By contrast, one should interpret the Llama License as involving the mutual exchange of consideration (the “bargained-for exchange”) between Meta and the user. That is, the contract is formed by the user’s assent to abide by the usage restrictions and the Acceptable Use Policy in the Llama License text in return for the privilege of using the AI model. Because a pure copyright license, by definition, extends only as far as copyright itself, it can impose only those restrictions recognized under copyright law. A contract grounded in general contract law, however, may permit the parties to expand their obligations beyond the scope of those intellectual property rights, creating stronger binding force and broader mutual duties.

Moreover, because the Llama License designates California law as the governing law, there is a possibility that contractual obligations could extend beyond the literal wording of the document. If the agreement contains somewhat ambiguous provisions, the courts generally interpret them according to the parties’ intent. Under such circumstances, a specific act may be deemed restricted if it aligns with the overall purpose or structure of the contract—even if the text does not expressly mention it. One must appreciate that this framework stands in stark contrast to Open Source licenses, where the user’s rights typically vest immediately upon receipt of the software.

2. Can Companies Disregard the 700 mil MAU Restriction? Concerns Regarding Aggregate User Counts

Answer: The 700 million MAU restriction affects more enterprises than commonly assumed and cannot be dismissed lightly.

Section 2 states:

“If, on the Llama 3.1 version release date, the monthly active users of the products or services made available by or for Licensee, or Licensee’s affiliates, is greater than 700 million monthly active users in the preceding calendar month, you must request a license from Meta …”

Section 2 of the Llama License explicitly stipulates that any enterprise with 700 million monthly active users (MAU) may not employ the Llama model without Meta’s express permission. In many jurisdictions, mention of Section 2 arises in debates over Llama’s compliance with Open Source principles, but the sheer figure of 700 million MAU often suggests that it applies only to a handful of major technology conglomerates in the United States or China, leading some to treat it as a remote concern. Yet is this clause truly irrelevant to large enterprises outside those countries?

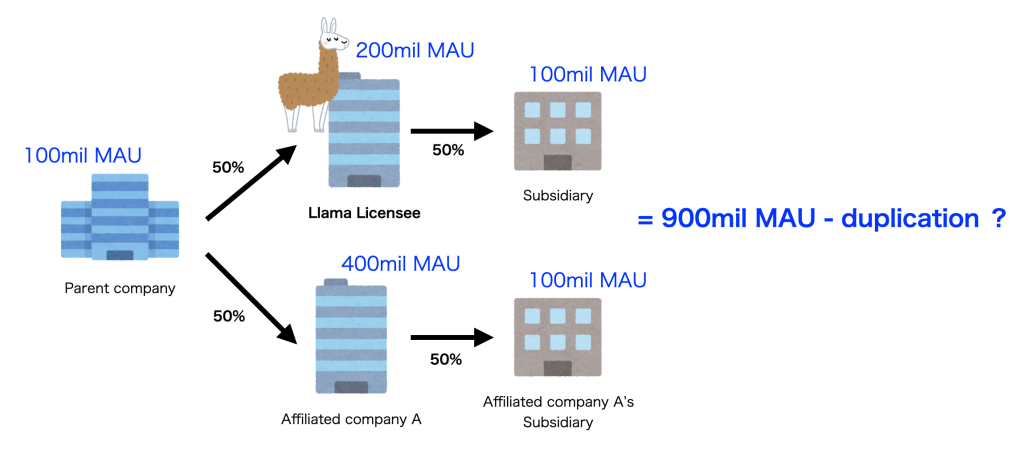

A closer reading clarifies that the restriction is not limited to the user count of a single service or product adopting Llama; rather, it is imposed on the entire corporate entity that becomes the user (Licensee). Furthermore, the phrase “Licensee’s affiliates” indicates that both subsidiaries and parent companies are included. Although the term “affiliates” is not defined within the contract text, it is typically construed to encompass all subsidiaries and parent entities connected by ownership interests of 50% or more. Under contracts governed by U.S. law, “affiliates” may, strictly speaking, also include partnerships and joint ventures, making the inclusion of “every entity with 50%-plus equity ties” an essential baseline. In a simple case, if there are four different services each with 200 million MAU and all are bound together by ownership interests exceeding 50%, then collectively they would total 800 million MAU, implying a potential breach of Section 2.

One might raise the objection that summing 200 million MAU four times, reaching 800 million, is unduly simplistic, ignoring the overlap of certain users. Indeed, that argument is valid. For instance, Meta itself, as the licensor, publicly announced in 2024 that it had 4 billion monthly active users across its entire corporate group, while separately stating that Facebook had 3 billion MAU, WhatsApp 2 billion, and Instagram 2 billion. The group’s declared total of 4 billion is thus markedly smaller than the simple arithmetic sum of each service’s MAU. Presumably, Meta is discounting duplicates in some manner. If that is the industry norm, then removing duplicates similarly would be a reasonable approach for other organizations. Yet in scenarios where no straightforward method exists to ascertain whether users across separate systems are identical (e.g., media services that do not require accounts), how can one accurately deduplicate user counts? It may in fact be “business-rational” to aggregate raw traffic analytics across multiple properties, thus elevating the apparent MAU.

Moreover, one might argue, for instance, that if the Licensee is a Japanese company, it could never surpass 700 million MAU, given Japan’s population of roughly 120 million. Perhaps that rationale holds for strictly domestic services using telecommunication lines subject to local demographics. Yet take Meta’s own self-reported 4 billion MAU figure. Considering a global population of approximately 8 billion, China’s population of around 1.4 billion (where Meta’s services are restricted), and roughly 2 billion people under age 13 worldwide, Meta is claiming that over 80% of all potentially eligible individuals across the globe use its services monthly. One might suspect that Meta’s declared MAU count is inflated relative to actual human individuals. Presumably, multiple accounts, business accounts, backups, and bots are contributing to the ostensibly inflated figures. In other words, Meta is indicating that “MAU” references account activity rather than distinct persons—a standard approach in social media. Consequently, a framework restricting MAU by reference to a particular real-world population of 120 million (for instance, that of Japan) fails to capture the realities of an open, globally-accessible platform or service.

Synthesizing these considerations, it seems plausible that enterprises beyond the recognized “tech giants” could still be impacted, especially where a large conglomerate spans multiple sectors or countries, lacks a robust system for eliminating duplicate user accounts across group companies, and collectively maintains services operating in various markets worldwide. Such an organization might, unintentionally, exceed the 700-million threshold established in Section 2, thereby contravening the Llama License if it employs Llama at a group-wide level.

In reality, for instance, a Japanese conglomerate focused on e-commerce but owning an Eastern European subsidiary that offers a telephony app with 800 million MAU could be subject to Section 2. Likewise, a Japanese HR-information enterprise that operates a U.S.-based job-search site with 500 million MAU could, once aggregated with other services, easily exceed the 700 million threshold. Similar scenarios arise for other conglomerates, and absent separate permission from Meta, they should presumably refrain from using Llama altogether.

One might attempt to craft documentation that shows, through careful calculation, fewer than 700 million total MAU across the group. However, if a CEO or CFO makes statements in an earnings call acknowledging that they surpass 700 million MAU, such an “admission against interest” under U.S. law carries substantial evidentiary weight in a lawsuit. From Meta’s perspective, it does not wish to allow Llama free of charge to an enterprise that could become a serious market competitor. Entirely apart from the details, the Llama License grants Meta unilateral power to claim “your group exceeds the threshold, so we are terminating this contract” if it wishes to do so. Consequently, large conglomerates are well-advised to avoid using Llama unless Meta grants explicit permission.

3. Do Mid-Sized or Smaller Enterprises Need Not Worry About the 700 mil MAU Restriction?

Answer: It would be mistaken to conclude that this threshold is wholly irrelevant to mid-sized enterprises.

One might suppose that if one’s enterprise group—or its presumed user base—falls below the threshold, the 700 million limit poses no concern. Consider the case of a smaller firm that develops Llama-based models or services. If it then seeks a merger or acquisition by a larger corporation already exceeding 700 million MAU, the larger entity may be barred from adopting Llama. From the vantage point of the smaller firm, that situation restricts the potential pool of M&A targets—thus making Llama usage itself a strategic risk.

Furthermore, consider a scenario in which a company develops a derivative Llama-based model and deploys it as part of a system or solution for a large conglomerate. The conglomerate’s right to use that derivative Llama-based model stems from the Llama License executed with Meta. Thus, as soon as the conglomerate implements the system or service, it must comply with the threshold, or it risks contravening Section 2. While Section 1.b.ii of the Llama License allows an exemption if the Llama Materials or derivative works are received as part of an “integrated end user product,” the contract text provides no precise definition of “integrated end user product.” One might interpret this provision to apply narrowly—perhaps only if the client does not have direct access to the Llama-based model’s code, for instance, as with a fully packaged product or a strictly hosted service. Thus, if a vendor undertakes development and then turns over ongoing operation of a Llama-based system to the client for in-house use, such a case would likely not qualify for the exemption. This is an especially important point of caution for Japanese businesses.

4. Must Subsidiaries, Parent Companies, or Affiliates Also Comply with the Llama Acceptable Use Policy?

Answer: It cannot be stated with absolute certainty that affiliated entities are invariably bound, but in many cases, compliance obligations effectively extend to all enterprises within a corporate group.

Section 2 of the Llama License establishes a threshold of 700 million monthly active users (MAU) for the Licensee. Under that provision, the scope of MAU calculation “expressly includes the Licensee’s affiliates,” indicating the entire corporate group in which companies are connected by ownership stakes of 50% or more. Beyond that paragraph in the Llama License text, there is no reference to affiliates that might imply a narrower interpretation. As a result, it can appear that the only reason to consider parent or subsidiary presence is for the purpose of aggregating MAU statistics.

Section 1.b.iv states:

“iv. Your use of the Llama Materials must comply with applicable laws and regulations (including trade compliance laws and regulations) and adhere to the Acceptable Use Policy for the Llama Materials (available at https://llama.com/llama3_1/use-policy), which is hereby incorporated by reference into this Agreement.”

Nevertheless, when read in concert with the rest of the contract, the situation changes. Under Section 1.b.iv, the Licensee is required to comply with the Acceptable Use Policy (AUP) whenever it uses the Llama Materials. Viewed in isolation, that clause seems aimed solely at the Licensee, but considered together with Section 2, one questions whether “Your use of the Llama Materials” might also extend to usage by affiliates.

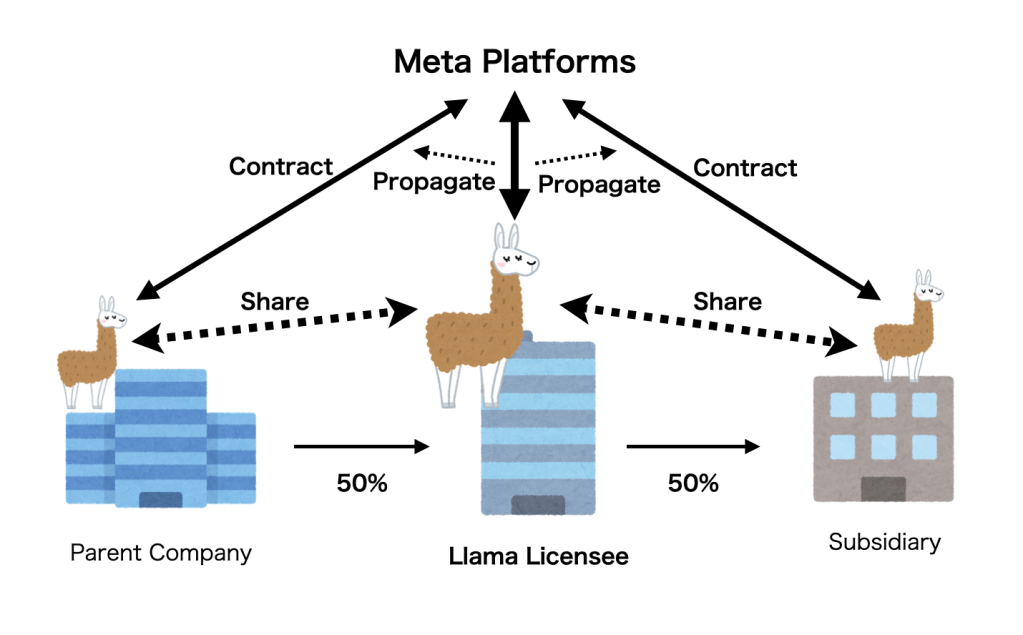

In many large corporate groups, it is common to share enterprise-level agreements for a given software or service among multiple entities within the same group. In the software industry, if a subsidiary has been formed as a separate development company, it is standard practice for the parent’s contract to encompass the subsidiary’s usage. There is nothing unusual in applying this rationale to an AI model like Llama. Hence, one could envisage a scenario in which both a parent company and its subsidiaries share a system built on Llama, thereby making the subsidiary (or parent) a direct user (or co-distributor) of the Llama Materials. Even if the parent entity itself did not originally download Llama from Meta, once it gains access through an affiliate’s derivative model, the parent entity would arguably enter a contractual relationship with Meta at the moment it begins to use the model. From the perspective of the Llama License’s “propagation,” such usage would naturally create an obligation for the parent company to comply with the AUP.

On the other hand, there are also instances where enterprises with 50% or greater capital ties operate in a genuinely independent manner. Should each company maintain clearly segregated operations, with no practical overlap in systems or usage, the question of group-wide compliance may never arise. Publicly recognized independence often means that one affiliate’s adoption of Llama would not implicate the rest.

Nevertheless, even if a parent-subsidiary relationship is effectively independent from the user’s standpoint, it may not be apparent to Meta. Should Meta suspect that Llama Materials have in fact been shared internally, it might view the entire group as effectively a single entity—particularly if it comes to light that some AI model usage contravenes the AUP in another affiliate. Section 6 of the Llama License grants Meta discretion to terminate the contract immediately if it deems the Acceptable Use Policy violated. In the event that Meta points to a group affiliate’s wrongdoing in using Llama, it could well argue that the same corporate group is a single integrated enterprise. Given the explicit mention of affiliates in Section 2 and the contract’s general “propagation” structure, it is not inconceivable that a court would uphold this position, effectively attributing the breach to the entire enterprise group.

Accordingly, in a large IT conglomerate as commonly seen in Japan, for instance, the group as a whole would be well-advised to verify that none of its subsidiaries are engaging in conduct barred by the Llama Acceptable Use Policy and to share any relevant compliance details internally. Such caution likely extends beyond Llama to other AI models that incorporate similarly broad contractual frameworks.

5. How Far Do Contractual Obligations and Compliance with the Acceptable Use Policy Extend?

Answer: Contractual obligations, strictly speaking, bind only the Licensee; however, the Acceptable Use Policy’s compliance requirements can effectively extend beyond the Licensee itself, impacting end users of any service that incorporates Llama.

Under Open Source licenses, the licensor unilaterally grants copyright permissions, and the duty to comply with its conditions applies only to users engaging in acts over which copyright law affords control—namely reproduction, distribution, adaptation, public transmission, etc. In other words, everyone is granted the right to use the software beforehand, and obligations arise only when such explicitly governed rights are exercised. A simple end user who merely “uses” the software, without implicating these statutory rights, typically incurs no license-imposed obligations.

By contrast, under the Llama License, the contractual framework is triggered whenever a party clicks “I agree” upon downloading Llama, or otherwise uses or distributes any part of the Llama Materials. At that point, both the downloader and any subsequent user enter into a bilateral contract with Meta, subject to the obligations set forth in the Llama License.

In practice, from the point of initial download by the first Licensee onward, there is little fundamental difference in obligation before or after actual usage. The key distinction emerges once Llama materials are distributed to third parties. Under the Llama License, if a Licensee obtains Llama from someone other than Meta, a direct contractual relationship with Meta nonetheless arises. Repeated distribution or modification may yield derivative Llama-based models distinct from the original, but each user employing such derivative models would be considered to have contracted with Meta at the moment of usage. This results in a chain of compliance akin to copyleft in principle—where every user of Llama-based materials, including derivative models, must adhere to the Llama License.

However, although the contract’s chain of compliance may spread along with the rising prevalence of Llama-based solutions, certain obligations (for instance, the non-transferability clause or brand-related provisions) relate specifically to uses implicating Llama Materials’ copyright. Merely “using” a derivative model might suffice to place the user under the Llama License, but brand constraints, for example, might not apply if the user does not distribute or publicly transmit the software in a way that triggers these obligations.

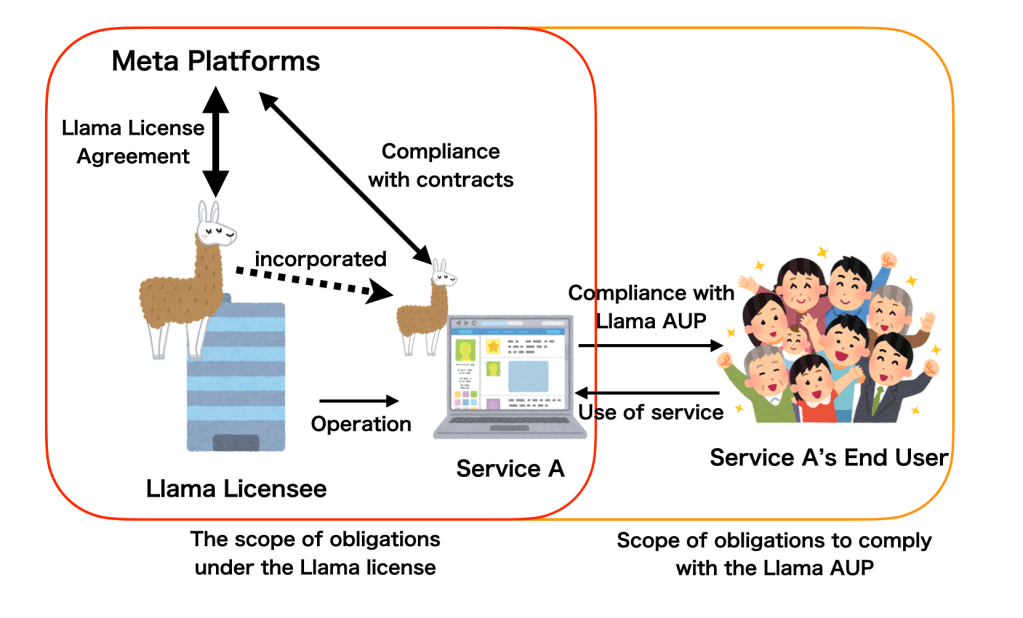

Nevertheless, as the Llama License explicitly incorporates the Acceptable Use Policy by reference, all Licensees must abide by the AUP when using Llama. The Acceptable Use Policy, by its nature, defines prohibited activities for the Llama model. Hence, any user subject to the Llama License must adhere to it. Importantly, however, this AUP compliance obligation may extend even further. If one incorporates a derivative Llama model into a system or service, the end users of that service may likewise be compelled—albeit indirectly—to comply with the Acceptable Use Policy.

Concretely, if a service built upon Llama is provided to customers who have no direct access to the Llama model itself, then no direct contractual relationship is formed between Meta and those customers. The service provider (the Licensee) remains the contracting party. Yet this service provider is still responsible for preventing user conduct that would breach the Llama Acceptable Use Policy—whether or not the user has direct access to the Llama model. In effect, the service provider must exert some measure of control over its customers’ behavior, ensuring that operation of the Llama-based system complies with the AUP. Technical measures might be employed for this purpose, but perhaps the simplest approach is to incorporate the entirety of the Llama Acceptable Use Policy (or an equivalent set of restrictions) into the provider’s own terms of service. Doing so effectively imposes the AUP’s compliance requirements on the end users as well.

As Llama’s user base expands, the resulting proliferation of “AUP compliance requirements” can magnify considerably. In this manner, Llama’s Acceptable Use Policy extends Meta’s capacity to govern usage far beyond the ordinary scope of a typical software license. Effectively, every participant in the chain—whether developers, service providers, or certain classes of end users—may find themselves bound to ensure compliance with the Llama Acceptable Use Policy.

6. Must New Clauses in the Acceptable Use Policy Be Observed If It Is Updated?

Answer: Any revisions Meta makes become binding at the time they are introduced, and must be obeyed accordingly.

Section 1.b.iv provides:

“iv. Your use of the Llama Materials must comply with applicable laws and regulations (including trade compliance laws and regulations) and adhere to the Acceptable Use Policy for the Llama Materials (available at https://llama.com/llama3_1/use-policy), which is hereby incorporated by reference into this Agreement.”

Section 1.b.iv. of the Llama License explicitly incorporates the Llama Acceptable Use Policy by reference. Contrary to the view that “the relevant version of the policy in force on the date specified at the top of the contract or on the date you downloaded the Llama Materials remains the only controlling version,” the correct interpretation is that “the policy document posted at the designated URL is always the effective Acceptable Use Policy.”

This logic is derived from contract-law principles: when a party consents to the Llama License, it does not merely agree to abide by the AUP as it existed at that instant, but also undertakes a continuing obligation to comply with any future amendments. In other words, the licensee receives the right to use the Llama Materials in exchange for accepting not just the current but also any subsequent version of the AUP. This arrangement is not unusual. In credit-card and insurance contracts, for example, terms are modified from time to time to reflect new circumstances or the passage of time, and customers continuing to use the service after a publicly announced revision are deemed to have accepted those revised terms. Within the AI domain, various licenses—Llama included—may similarly employ an Acceptable Use Policy, and with the ongoing emergence of legal and regulatory concerns worldwide, there is arguably a need for frequent changes to keep pace with new risks or issues. Each such development may justify strengthening or expanding the policy’s requirements.

Of course, there are some legal restrictions on unfair or arbitrary changes to the Acceptable Use Policy by Meta. However, so long as the updates serve a legitimate contractual purpose and do not fundamentally alter the transaction’s nature—moreover, so long as they are clearly communicated to licensees—the courts are likely to support Meta’s revisions even if they are challenged. Under California law, which places greater emphasis on “clearer notice” and “commercial reasonableness” than on extended consumer protection or dual consent, the notification period for policy updates may be shorter than one might expect under Japanese law. Consequently, Llama users—especially Japanese businesses—should remain aware that Meta can update the Llama Acceptable Use Policy at any time and avoid relying too heavily on domestic expectations of how such notices or revisions typically function.

7. What Risks Arise When the Acceptable Use Policy Is Updated?

Answer: Meta may at any time add provisions disadvantageous to a particular enterprise or force that enterprise to cease usage.

While the Llama Acceptable Use Policy broadly bans illicit or unethical behavior relating to content generation, user manipulation, or system integration with outside tools, Meta can also introduce measures—ostensibly neutral, rational, and safety-oriented—that could impose considerable burdens on the licensee.

For instance, under the guise of safety or regulatory compliance, Meta might require complete user-activity logs within any Llama-based system. It could also mandate strict content filtering or analytics tools, thereby raising the licensee’s operational costs. If Meta were additionally to demand that only Meta-approved tools be used to facilitate such compliance, that could raise licensees’ overall compliance costs even more. Such requirements appear, at a glance, to be valid steps to improve transparency, making them notably troublesome to refute.

Meta could also leverage cultural or legal differences among jurisdictions. For example, if a new clause were added stating, “Model outputs must, even for fictional characters, conform to U.S. content standards,” one might speculate that it could negatively affect industries like anime, manga, or gaming in Japan. Already, there has been an incident where Visa halted card transactions for content generally considered lawful and ethically acceptable in Japan, viewing it as an ethical issue. A similar scenario could arise here.

Some might assume that a publicly traded entity such as Meta would not engage in these types of extreme actions. Indeed, no updates have thus far been introduced retroactively to the Acceptable Use Policy for an already-released version of Llama. However, upon the release of Llama 3.2, certain clauses were quietly added in comparison to Llama 3.1, framed as “reasonable AI safety measures,” which could ultimately restrict otherwise legitimate behavior. For instance:

“h. Engage in any action, or facilitate any action, to intentionally circumvent or remove usage restrictions or other safety measures, or to enable functionality disabled by Meta”

“5. Interact with third party tools, models, or software designed to generate unlawful content or engage in unlawful or harmful conduct and/or represent that the outputs of such tools, models, or software are associated with Meta or Llama 3.2”

Clause 1.h., for instance, prohibits bypassing technical restrictions placed on the Llama model, potentially interpreted as barring researchers from investigating or testing Llama’s behavior. Even if a licensee merely wanted to evaluate Llama’s safety by removing certain technical constraints, Meta could invoke that clause to terminate the license. Additionally, Clause 5 prohibits integrating with “harmful tools” or labeling the outputs as originating from Llama, which might hamper legitimate research or transparency measures about potentially harmful interactions with Llama—leading instead to a broader range of justifications for Meta to end the contract.

“With respect to any multimodal models included in Llama 3.2, the rights granted under Section 1(a) of the Llama 3.2 Community License Agreement are not being granted to you if you are an individual domiciled in, or a company with a principal place of business in, the European Union.”

Even assuming that Clauses 1.h. and 5 can somehow be defended under safety or ethical grounds, the additional restriction on multimodal models for EU citizens and businesses reveals a major trap inherent in the Llama License. Typically, an Acceptable Use Policy enumerates prohibited usage scenarios and is aimed at restricting how the software is applied. Yet this EU-specific clause outright bars EU residents and companies from obtaining any rights to use such Llama models. One might have expected that a license’s grant or denial of usage rights would appear in the main contract text, but placing such provisions in an Acceptable Use Policy highlights Meta’s prerogative to withhold usage from any region or organization. While Meta’s motive—circumventing European AI regulation—may be understandable, that clause also shows that Meta has the de facto power to terminate Llama usage for any disliked country, corporation, or community.

While the Llama Acceptable Use Policy mainly consists of prohibitions, all of these “traps” could allow Meta to channel organizations into another proprietary contract. This tactic resembles the dual-licensing or open-core model seen in certain Open Source contexts. Thus, Meta adopting a revenue-generating arrangement under the guise of compliance is by no means implausible.

8. May One Apply Local Law in Interpreting the Acceptable Use Policy?

Answer: In principle, U.S. law and practice (particularly California law) govern.

Section 7 provides:

“7. Governing Law and Jurisdiction. This Agreement will be governed and construed under the laws of the State of California without regard to choice of law principles, and the UN Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods does not apply to this Agreement. The courts of California shall have exclusive jurisdiction of any dispute arising out of this Agreement.”

Section 7 of the Llama License explicitly selects California law “without regard to choice of law principles,” thus precluding other jurisdictions from applying their laws. Because the Acceptable Use Policy is “incorporated by reference” as part of the contract, it too is governed by California law.

Comparing Japanese and U.S. approaches reveals numerous differences in the interpretation of intellectual property and contract law. As previously explained regarding modifications to usage terms, Japan’s stricter stance on unilateral changes to contract conditions may lead local parties to underestimate the risks. Under the Llama License, if Meta imposes AUP clauses that reflect cultural or legal norms of the United States, disputes must be settled promptly under California law. Topics such as fictional depictions of underage characters, privacy/data protection, and content moderation might differ widely across jurisdictions; in all cases, the Llama License compels U.S.-centric standards.

Accordingly, an overseas enterprise remains bound by California law when interpreting the AUP, and must impose matching constraints on its service’s end users if it deploys Llama. Even a purely back-end Llama-based system for end users in Japan would be subject to the Llama License, from which Meta draws rationales under California law. This single set of interpretative rules may appear convenient from Meta’s vantage point, allowing for a uniform approach to compliance worldwide.

9. Does the Llama License Extend to Model Outputs and Models Trained on Those Outputs?

Answer: Although Meta has not explicitly stated as much, it appears to adopt the position that even synthetic data derived from Llama’s outputs may be subject to the Llama License.

“Llama 3.2” means the foundational large language models and software and algorithms, including machine-learning model code, trained model weights, inference-enabling code, training-enabling code, fine-tuning enabling code and other elements of the foregoing distributed by Meta at https://llama.com/llama-downloads.

“Llama Materials” means, collectively, Meta’s proprietary Llama 3.2 and Documentation (and any portion thereof) made available under this Agreement.

By way of explanation, we note first that in the contract text’s initial definitions, Llama 3.2 and Llama Materials are described as above. “Llama 3.2” refers to the model itself—weights, code, and algorithms—while “Llama Materials” encompasses the entire model and its documentation. Some might read this to cover only the model and its documentation; however, due to the effect of the word “collectively,” Llama Materials arguably need not be limited to merely those two items. Instead, it could expand to include training data, derivative models, API access, or technical support (provided no legal impediments to including them under “Llama Materials” exist).

Section 1.b.i states in relevant part:

“If you distribute or make available the Llama Materials (or any derivative works thereof), or a product or service (including another AI model) that contains any of them, you shall (A) provide a copy of this Agreement … and (B) prominently display ‘Built with Llama’ … If you use the Llama Materials or any outputs or results of the Llama Materials to create, train, fine tune, or otherwise improve an AI model, which is distributed or made available, you shall also include ‘Llama’ at the beginning of any such AI model name.”

Crucially, Section 1.b.i parallels “Llama Materials” with “any outputs or results of the Llama Materials” when establishing an obligation to prepend “Llama” to any derivative AI model’s name. By juxtaposing the model itself with its generated outputs, this clause unequivocally places both under comparable obligations, thereby clarifying that the contract’s scope extends to the model’s generated results as well. In other words, it is feasible to interpret that even absent explicit language specifying “Model outputs are deemed Llama Materials,” such outputs are subsumed under the license’s terms and thus carry licensing obligations.

Further support comes from Section 1.b.iv, which dictates that “use of the Llama Materials must comply with applicable laws and regulations … and adhere to the Acceptable Use Policy,” and that Acceptable Use Policy likewise addresses the usage of outputs. Moreover, Section 5.c includes language referencing situations in which “Llama Materials or Llama 3.2 outputs or results, or any portion of the foregoing, infringe upon your intellectual property or other rights.” By placing model outputs on a level with the model itself, Meta signals a legal equivalence between them. Under U.S. contract law, this logic can be readily explained, and indeed Meta has published datasets on Hugging Face containing results of benchmark testing with Llama; these datasets carry the Llama License terms, illustrating Meta’s practical stance that the license extends to Llama’s outputs.

From that reasoning, one might conclude that the Llama License propagates through Llama’s outputs. Should one compile those outputs into a synthetic dataset and employ that dataset to train another AI model, it follows that both the dataset itself and the AI model might be encumbered by the Llama License. This scheme significantly surpasses the conventional bounds of copyleft grounded in copyright law; one is effectively creating a “chain of contractual obligations” that can extend well beyond typical software licensing structures.

Nevertheless, the idea that Llama’s license coverage might extend through synthetic data raises nontrivial legal uncertainties. In many jurisdictions, no definitive precedent establishes whether probabilistic outputs can (or should) retain a model’s legal status. For instance, if someone posts Llama outputs to a blog, and those outputs eventually find their way into another AI’s training data, it seems improbable that Meta would assert the Llama License for something so attenuated. Yet if a party intentionally aggregates a large body of Llama-generated content to train a new model, Meta’s interpretation might demand that the new model be subject to the Llama License—and, contractually speaking, that is arguably the more natural reading.

Equally noteworthy is that this concept of “license transmission via synthetic data” would be relevant for any other AI license or contract the new model might have. If the new model was originally under a permissive Open Source license, no fundamental conflict arises; but if another license with conflicting Acceptable Use Policy provisions applies, those divergences may create irreconcilable conditions. For instance, the Llama License’s naming obligations (requiring “Llama” to appear at the front) or usage constraints could conflict with other license terms. Where obligations under multiple agreements cannot all be fulfilled, the user must abstain from using one or both. While naming restrictions are a likely point of friction under Llama, contradictory usage restrictions in the respective Acceptable Use Policies also present a real possibility.

10. Conclusion

Despite failing to meet the standards of Open Source, the Llama Community License Agreement is sometimes extolled as a free, “ethically guided” model intended to ensure transparency and reliability in AI. Yet, as explained above, several attributes of the Llama License—its user-threshold restriction based on commercial scale, a powerful Acceptable Use Policy subject to unilateral amendment, and a level of contractual propagation surpassing copyleft for data outputs—go far beyond typical software licensing. Many organizations or individuals may assume they are obtaining a cost-free open model, not realizing that it effectively imposes behavioral controls on virtually every user down the line, including users of derivative models.

It is therefore essential for any entity considering the use of Llama to read its license and Acceptable Use Policy closely and to monitor them on an ongoing basis. A failure to do so could jeopardize the organization’s business operations or reputation if Meta were to terminate the license abruptly.

References

- Llama 3.1 Community License Agreement https://www.llama.com/llama3_1/license/

- Llama 3.1 Acceptable Use Policy https://www.llama.com/llama3_1/use-policy/

- Llama 3.2 Community License Agreement https://www.llama.com/llama3_2/license/

- Llama 3.2 Acceptable Use Policy https://www.llama.com/llama3_2/use-policy/

- Llama 3.3 Community License Agreement https://www.llama.com/llama3_3/license/

- Llama 3.3 Acceptable Use Policy https://www.llama.com/llama3_3/use-policy/

- Original Japanese Article: https://shujisado.com/2025/01/20/llama_license_risk/